In this continuation of Frederick Douglass’s account of his

1842 visit to Pittsfield, N.H. (part one here), he tells of his encounter with Moses Norris Jr.

and mentions an earlier episode involving Norris and George Storrs. A brief primer

about these men and about certain events involving them might be helpful.

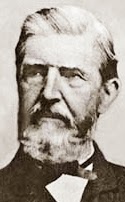

Norris was 42 years old when the 24-year-old Douglass came

to Pittsfield. He was a local lawyer and Democratic state representative at the

time.

|

| Moses Norris Jr. |

Norris’s clash with George Storrs, an itinerant Methodist minister,

had occurred six years earlier on March 31, 1836. The U.S. House was weeks away

from adopting a gag rule to block further debate and discussion of abolition in Congress. After preaching against slavery in a Pittsfield pulpit, Storrs was

arrested as another pastor was giving the closing prayer of the service. The warrant

accused him of being “a transient person” and “a common railer and brawler

against the dignity of the State.”

Norris prosecuted the case the same day. The judge convicted

Storrs and sentenced him to serve three months at hard labor in Pittsfield’s

House of Correction and to pay the $15.80 cost of the prosecution. An appeals

court dismissed the case.

Norris was elected to Congress in 1842, the year he met Douglass, and later

to the U.S. Senate. As a congressman, he opposed efforts to check the extension

of slavery to new states. He accused abolitionists of having “liberty and philanthropy on the

folds of their flag [while] arming themselves to overthrow the Constitution and

break up the Confederacy.” He died in 1855 and is buried in Floral Park

Cemetery in Pittsfield.

We pick up Douglass’s story in the Old Meeting House Cemetery, next to the building where he has just spoken. It is drizzling and he is alone, hungry and tired. He reflects that at least in a cemetery there is “an end to all distinctions between rich and poor, white and colored, high and low.” This account comes from The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass:

|

| The abolitionist George Storrs, a native of Lebanon, N.H., became a supporter of the Millennialist preacher William Miller. |

“While thus meditating on the vanities of the world and my

own loneliness and destitution, and recalling the sublime pathos of the saying

of Jesus, ‘The foxes have holes, and the birds of the air have nests, but the Son

of Man hath not where to lay his head,’ I was approached rather hesitatingly by

a gentleman, who inquired my name. ‘My name is Douglass,’ I replied. ‘You do

not seem to have any place to stay while in town.’ I told him I had not. ‘Well,’

he said, ‘I am no abolitionist, but if you will go with me I will take care of

you.’ I thanked him, and turned with hi toward his fine residence. On the way I

asked him his name. ‘Moses Norris,’ he said. ‘What! Moses Norris?’ I asked. ‘Yes,’

he answered. I did not, for a moment, know what to do, for I had read that this

same man had literally dragged the Reverend George Storrs from the pulpit for

preaching abolitionism. I, however walked along with him, and was invited into

his house, when I heard the children running and screaming, ‘Mother, mother,

there’s a nigger in the house! There’s a nigger in the house!’ and it was with

some difficulty that Mr. Norris succeeded in quieting the tumult. I saw that

Mrs. Norris, too, was much disturbed by my presence, and I thought for a moment

of beating a retreat; but the kind assurances of Mr. Norris decided me to stay.

|

| A plaque in Pittsfeld marks the place where Moses Norris and Frederick Douglass met. |

“I spoke again in the evening, and at the close of the

meeting there was quite a contest between Mrs. Norris and Mrs. Hilles as to

which one I should see home. I considered Mrs. Hilles’ kindness to me, though

her manner had been formal. I knew the cause, and I thought, especially as my

carpet-bag was there, I would go with her. So giving Mr. and Mrs. Norris many

thanks, I bade them good-bye., and went home with Mr. and Mrs. Hilles, where I

found the atmosphere wondrously and most agreeably changed. Next day, Mr.

Hilles took me, in the same carriage in which I did not ride on Sunday, to my next appointment, and on the way told me

he felt more honored by having me in it than he would if he had the President

of the United States. This compliment would have been a little more flattering to

my self-esteem had not John Tyler then occupied the Presidential chair.”

George Storrs later was asked to leave the Methodist ministry over two issues: his vocal anti-slavery stand, and his preaching of "conditional immortality" as opposed to inherent immortality of the soul. His teaching on the latter was a great influence on Charles T. Russell, founder of the Bible Student Movement (from which the modern-day Jehovah's Witnesses, among other groups, derived), and also on various groups within the Adventist movement, including the Seventh Day Adventists.

ReplyDelete