Some elections matter more than others. The 1863

gubernatorial election in New Hampshire mattered, to the state as well as the

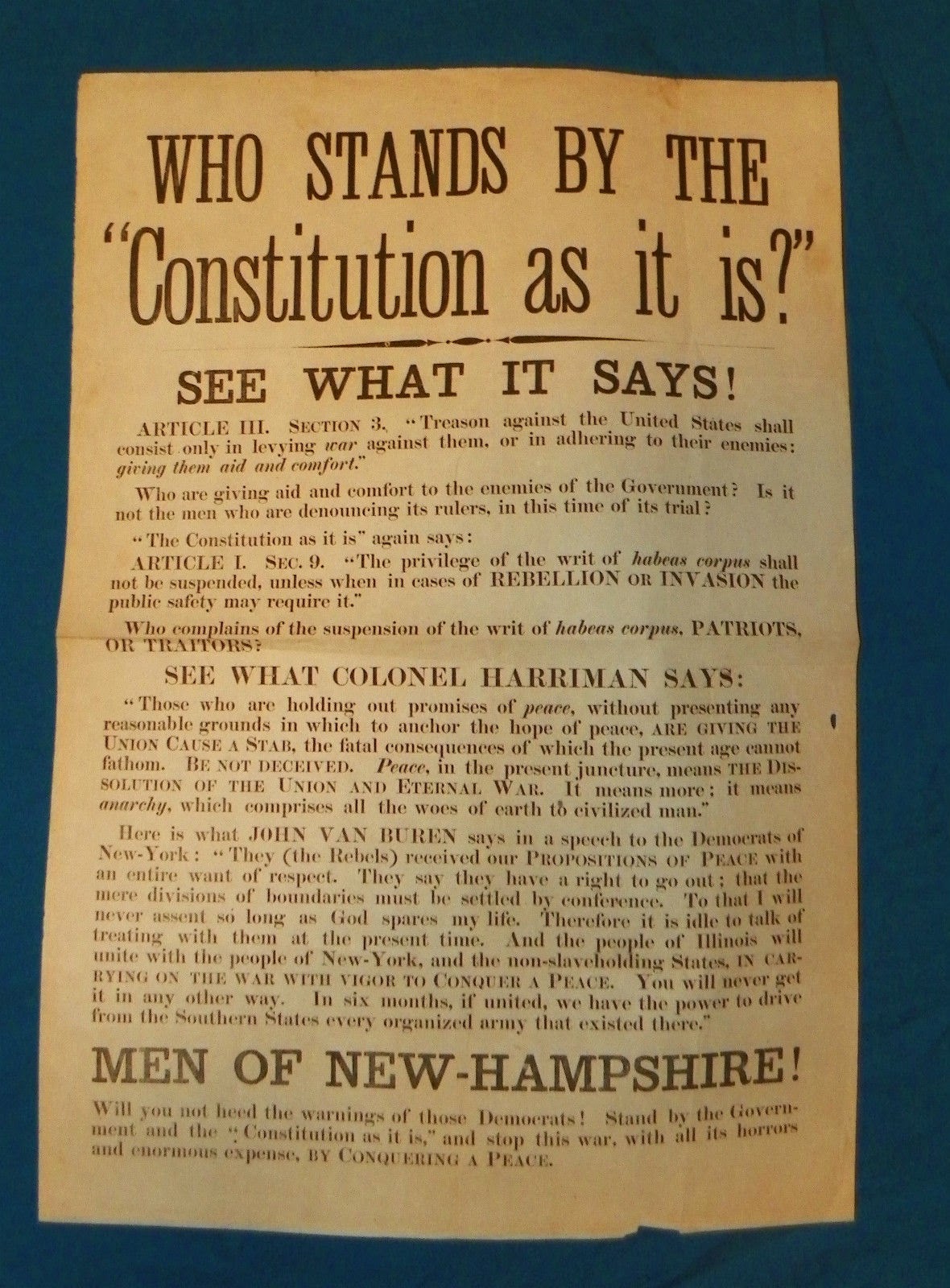

nation. Below this post is a broadside that sold on eBay the other day. Behind it is the

story of that election.

The Republicans had held the governor’s office through 18

months of war, but they were in danger of losing it in 1863 – and they knew it.

The Union army had just been defeated at Fredericksburg. The Democrats were

howling over the fratricidal war and President Lincoln’s liberal interpretation

of his constitutional war powers. “The Constitution as it is” was a Democratic slogans.

|

| Walter Harriman |

Because states controlled the raising of soldiers, the

Lincoln administration wanted a friend in every northern governor’s office. New Hampshire Republicans were so rattled by worries

about defeat that they considered nominating a pro-war Democrat for governor.

They also invited Edward E. Cross, colonel of the 5th New

Hampshire and a feisty Democrat who had been badly wounded twice, to speak at

their nominating convention on New Year’s Day in 1863. Since May, Cross’s regiment had fought at Fair

Oaks, in the Seven Days battles, at Antietam and at Fredericksburg.

The War Democrat the Republicans invited to run for governor

was Walter Harriman, colonel of the 11th New Hampshire. Like the 5th, the 11th had

just suffered losses in the fiasco at Fredericksburg.

Harriman turned them down. He sent his rejection through A.P. Davis, a delegate to the convention from Warner, where Harriman also lived. “Having understood that some of my personal friends propose to compliment me with their votes in the convention of January 1st for the nomination of a candidate for governor, I address you this brief line to say I can by no means be considered a candidate,” Harriman wrote.

Harriman turned them down. He sent his rejection through A.P. Davis, a delegate to the convention from Warner, where Harriman also lived. “Having understood that some of my personal friends propose to compliment me with their votes in the convention of January 1st for the nomination of a candidate for governor, I address you this brief line to say I can by no means be considered a candidate,” Harriman wrote.

In the American political tradition of ignoring such

demurrals, a Republican delegate nominated Harriman anyway. On the first ballot

Joseph A. Gilmore received 276 votes, but Harriman came in second. Gilmore, a

railroad magnate from Concord, won a majority and the nomination on the second

ballot, but Harriman’s vote total rose from 96 to 155.

This outcome no doubt influenced what Harriman did

next. When Republican friends, fearful of defeat in the March 10 election,

asked him to enter the race as a third-party candidate – a War Democrat –

Harriman said yes. If he could steal votes from Peace Democrats, he was glad to

oblige as long as “Democrat” appeared next to his name. On February 17, three

weeks before the election, the Union Party met in Manchester and unanimously

nominated him.

Writing to a Manchester newspaper editor from Newport News,

Va., on Feb. 25, Harriman spelled out his reasoning. In the broadside below, printed

and distributed during the waning days of the campaign, the Republicans used Harriman’s

words from this letter in an effort to get out their vote. The broadside suggested

to voters that it was not the Democrats who were embracing the Constitution but the Republican Party and the pro-war faction of the

Democratic Party.

“Those who are holding out promises of peace, without

presenting any reasonable grounds for the hope of peace, are giving the Union

cause a stab, the fatal consequences of which the present age cannot fathom,”

the broadside quoted Harriman. “Be not deceived. ‘Peace,’ in the present

juncture, means the disunion of the Union and eternal war. It means more; it

means anarchy, which comprises all the woes of earth to civilized man.”

Harriman also wrote in the Newport News letter: “My duties

and cares are military, and not political.” But because the convention has

stated “sentiments substantially my own, and unanimously invited me to bear, in

the present campaign, the old flag of the Union, I hardly feel at liberty to

withhold the use of my name. . . .

“Our country is on the very brink of ruin; let us suppress

every thought except the one patriotic desire to benefit and to save it.”

To show that Southerners were finding comfort “in the

diseased condition of Northern sentiment,” Harriman quoted William L. Yancey, a

Southern fire-eater. Yancey had written: “We have something to hope, however,

from this division of the councils of our enemies – from their fierce party

strife and jealousies; upon this hope let us build our own unity; upon their

jealousies let us build our own harmony; upon these clashings of party interest

let us bind together our patriotic energies.”

The broadside below took up Harriman’s themes. It urged that

New Hampshire voters recognize southern treason and cast their votes for

upholding the Constitution and bringing about peace by winning the war.

In the end Harriman’s third-party candidacy did just well

enough to deny the Democratic gubernatorial candidate a majority. You can read

that story here and here.

No comments:

Post a Comment