Below is my column for today’s Concord (N.H) Monitor about

Donald Sterling’s lifetime ban from the National Basketball Association. As you’ll

see, it is really about how recently racist and homophobic language was common

in New Hampshire politics.

|

| Lucy Hale |

In the column I pick on Jack Chandler, a longtime New

Hampshire pol who has been dead since 2001, but I could have cited others

involved in 1980s and ’90s debates over such issues as the Martin Luther King

holiday and gay rights.

One thing Chandler had that the others didn’t was a blood

relationship with John Parker Hale, a pioneer in the political fight against

slavery from the mid-1840s through the Civil War. Considering Chandler’s heritage, his racism struck me as an irony.

Just to add a few details to the column, Hale’s daughter,

Lucy Hale, was Jack Chandler’s grandmother. She is best known for her relationship

with John Wilkes Booth during the months leading up to the Lincoln assassination.

She later married William E. Chandler, an early and prominent Republican who

served in the Cabinet of Chester A. Arthur and in the U.S. Senate.

Here’s the column:

With what stunning speed did the National Basketball

Association distance itself from the racist comments of Donald Sterling, owner

of the Los Angeles Clippers. Lots of money was at stake, of course, but the

lifetime ban demanded by Adam Silver, the new league commissioner, was a

milestone in America’s long history of racism and tolerance of racist speech.

If you don’t think we’ve come a long way in a short time,

consider the case of John P.H. Chandler, a New Hampshire state senator from

Warner.

|

| John Parker Hale |

Each day he went to a Senate or House session or Executive

Council meeting during his decades in office, Chandler walked past a statue of

his namesake and great-grandfather. Chandler’s full name was John Parker Hale

Chandler. The statue exists because John Parker Hale risked his political skin

to oppose the westward extension of slavery in the 1840s.

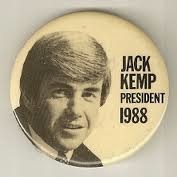

In 1987, John P.H. Chandler chose Rep. Jack Kemp as his

candidate in the presidential primary. Kemp rewarded him by naming him honorary

Merrimack County chairman for the campaign.

Chandler repaid Kemp by repeating the same racist joke at

several events. The butt of it was Jesse Jackson, who ran an excellent campaign

that year for the Democratic nomination. Chandler’s joke went: “Did you hear

that Jesse Jackson has dropped out of the presidential race? He found out that

his grandmother had posed for the centerfold of National Geographic.”

Kemp asked Chandler to apologize publicly, but Chandler

declined. In conversations with reporters he expanded on his thoughts.

He almost vomited when he saw Jackson kiss the white

daughter of a campaign official, he said. “It just seems to me that each race

should keep themselves pure. If we have too much race mixing, it’s going to

wipe out the white race. We’re far outnumbered by the blacks, browns, yellows.”

Kemp had more African-American friends and colleagues than

any other Republican presidential candidate that year. A Monitor story

documented how, as quarterback of the Buffalo Bills, he had earned the respect

of his teammates of all races.

Kemp cut Chandler from his political team.

New Hampshire officials were a bit more tepid about

Chandler’s remarks. Gov. John H. Sununu called his words “unfortunate,

inappropriate,” but Elsie Vartanian, the state party chief, said: “The voters

have returned him on a regular basis (and) will decide whether they want to do

that again.”

As Vartanian’s statement indicated, Chandler’s comments were

not isolated. He had been saying such things for years, and he wasn’t the only

one.

To recall further what was acceptable political rhetoric in

those days, it is worth considering what Chandler said that year in the clubby

atmosphere of the Republican-dominated state Senate.

|

| Martin Luther King Jr. before the crowd on the mall in Washington, Aug. 28, 1963. (AP photo) |

One issue was the Martin Luther King holiday, which

President Ronald Reagan had signed into law in 1983. States had the option of

adopting the holiday or not, and New Hampshire debated it annually.

“Happy Jack,” as Chandler was known, was the Senate’s

president pro tem. He called the King bill “absolutely a ridiculous piece of

legislation.” King’s organization was riddled with communists, he said. “He

socialized with communists” and refused President John F. Kennedy’s pleas to

stop doing so.

“The FBI had him under surveillance for years,” Chandler

said of King. “The head of the FBI, Mr. Hoover, called Martin Luther King the

greatest liar in the country.” After King was assassinated in 1968, Chandler

claimed, the FBI hid away its records. These records, he said, would one day

show “the bad things that he did. He was an evil, immoral man.

“He claimed to be a man of peace. But everywhere he went he

caused a riot, a lot of times people got killed as a result of his activities.

. . . To consider a man like this, to honor him for a holiday, is insane in my

opinion. I hope that this honorable Senate will never vote for such a bill.”

The Senate rejected the holiday 14-9. Chandler and other

King haters remained a national embarrassment for a dozen more years.

In 1999, New Hampshire became the last state in the union to

adopt Martin Luther King Day.

Chandler’s comments on gay and lesbian foster parenting that

year were of a similar nature. He had first attempted to prohibit “homosexuals”

from giving blood, famously saying it was okay for them to donate it as long as

they donated it all.

This bill morphed into one prohibiting foster parenting by

gay men and lesbians.

“It’s a horrible idea to take young children of either sex

and put them into a foster home that is run by two homosexuals or one

homosexual,” Chandler said. “Like night follows day, that child would be in some danger to be in

some environment like that. . . . I wouldn’t want any grandchild or

great-grandchild of mine to be in such a home, and I don’t think that any

person in their right mind would want that either.”

Although that term turned out to be Chandler’s last in

public office, he got a pass for such language because racism and homophobia

were still acceptable parts of the great American political tradition.

Now people can have such thoughts, but they express them at

their peril.

The spectacle of an NBA team owner caught making racist

remarks – and the price he will pay for them – is only the latest sign of this

change.

It’s about time.

It’s about time.

Here's a good letter to the editor of the Monitor responding to this column. The writer is the Warner, N.H., librarian:

ReplyDelete"Mike Pride states that in the 1980s, Jack Chandler 'got a pass for (his) language because racism and homophobia were still acceptable parts of the great American political tradition' (Monitor Forum, May 1) and that the term in which Chandler made outrageous remarks about gays and presidential candidate Jesse Jackson 'turned out to be his last.'

I would like to point out that Chandler’s comments and attitudes were the reason why he was firmly rejected by the voters in his district the next time they had a chance to vote. Perhaps Chandler’s outrageous statements were acceptable to, or part of the 'political tradition' of John Sununu and GOP party chair Elsie Vartanian, as Pride implies, but not to voters in Chandler’s district.

Much as we in New Hampshire accept variety and choose to overlook odd or offensive remarks by well-known members of our community, Chandler went way over the top in his last term, and thanks to the Monitor’s thorough and candid coverage, everyone was made aware of it and took action to ensure he no longer 'represented' us.

NANCY LADD

Warner