During my research for Our

War, I saw the same sentiment in the soldiers’ letters as the Civil War

ground on. For my final chapter I went looking for a man who represented this

near-universal wish of soldiers in all wars.

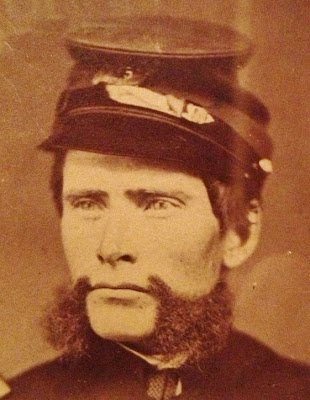

The man I found was Ransom Sargent of New London, a fifer in

the 11th New Hampshire Volunteers. Sargent married a local woman, Maria French,

in August of 1862 and mustered into his regiment 17 days later. Then, for more

than a thousand days, he did not see her.

Sargent’s letters to Maria, transcripts of which are in the

Rauner Special Collections at Dartmouth College, often express his yearning to

touch her or look into her eyes. In 1865, as the war neared its end, he wrote:

“Oh!

I could read your thoughts sometimes, dear Maria, and what joy it gave me for I

knew that tender look of passion was bestowed only on me. You are my only hope

of happiness in the future. All my plans and bright anticipations could never

be realized if you did not share my joys.”

My

chapter on Sargent, called “Homecoming,” has three points: the “I just want to

go home” attitude of the soldiers, the transition from war to peace on the home front, and the efforts of the citizenry to welcome the soldiers home.

Two

recent events, one personal, the other a local news item, reminded me of this “Homecoming”

chapter.

The

personal event was an encounter at a restaurant with a stranger around my

age who was wearing a Florida Gator cap. I told him I had gone to Florida, and

he asked me when. I said I had only attended for two years during the Vietnam

era, then been drafted. He said, “Thank you for your service.”

That

is a common expression these days, but no one had ever said it to me. I thanked

the man for thanking me. But as sincere as I meant to be, neither his thanks

nor my response altered my feelings about coming home in 1970.

Then

I began to read about an event in Concord tomorrow to welcome home Vietnam

veterans. I hope lots of veterans and citizens show up, and I hope the veterans

feel the love.

I

am not a veteran of that war. I served in the army at its height, but rather

than accept the draft, I enlisted for four years in exchange for a guarantee of

language school. I learned Russian, trained on special radios, and went to Germany to

intercept and analyze Soviet military communications in East Germany.

In

early 1970, I married Monique Praet, a Belgian teacher I had met in Germany. A

short time later, I received orders to come home. I had been in Germany for two

years by then. It had been a terrible time for my country, marked by unending,

unwinnable war, political violence and assassination. I, meanwhile, had come to

appreciate the European mentality, which, for obvious reasons, was skeptical of

war.

I

packed my duffel bag, put on my dress uniform and caught my flight home in

Frankfurt. Monique flew to Florida, where my parents lived. My military flight

landed early in the morning at McGuire Air Force Base in New Jersey. There we

boarded buses for the Philadelphia airport for flights to our next stations. Mine

was Fort Gordon, near Augusta, Ga.

.jpg) |

| My mother Bernadine with Monique and me outside the military chapel near Cologne,Germany, where we were married on Jan. 31, 1970. |

That

morning in the Philadelphia airport was my homecoming, and I will never forget

it. From

the moment I walked in wearing my uniform, the civilians in their double-knit suits

and bell-bottoms, miniskirts and flowery blouses, had two reactions to my

presence. Some looked at me with scorn, as though I had just returned from

spearing Vietnamese babies and hoisting them on my bayonet. The others

stared straight through me. I felt hated, invisible.

The moment I realized my uniform made me a pariah, I found a restroom and changed

into civvies.

The

ironies of this experience were thick. I had never been to Vietnam. While many

of my brothers-in-arms had, and while I admired their courage, I knew many –

perhaps most – had gone to war against their will. Personally, I had always opposed the

Vietnam War and identified with the peace protesters.

In

the last months of my enlistment, one of my duties was the funeral detail. I

was on the firing squad for the burial of half a dozen men killed in Vietnam. More

than 40 years later, thinking about this can still move me to tears.

I

hope the Vietnam War veterans who turn out tomorrow find some satisfaction and

closure in Concord’s belated welcome.

As

for my Civil War fifer, Ransom Sargent, he marched and played in two parades in

downtown Concord in June 1865, and he wasn’t thrilled about it. “They kept us

parading up and down the street until dark, as tired as the men were,” he wrote

Maria Sargent after the first one. He thought – hoped – the next day’s parade might be rained

out, but no such luck.

When

it was over, the burning ambition of nearly every soldier came true for Ransom Sargent: He

hopped a train to New London 30 miles away and went home to his Maria.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

+pliney.jpg)

.jpg)