A Civil War letter came to hand this week that reminded me

of a surprising, if macabre, discovery during research years ago. Mark Travis and I found the note in question at Carlisle Barracks, Pa., while working on My Brave Boys, a history of Col Edward

E. Cross and the 5th New Hampshire Volunteers.

|

| Miles E. Peabody died in 1864. |

Private Miles E. Peabody, who lived along the North Branch

of the Contoocook River in Antrim, became a prominent character in the book

because he had written so many letters. In one batch of them, we turned up a note written after Peabody died of disease in

1864. A fill-in-the-blanks form letter from his embalmers, it had been attached to his coffin before it was shipped home.

The note was intended for either the undertaker in New

Hampshire “or friends who open this coffin.”

It read:

“After removing or laying back the lid of the coffin, remove

entirely the pads from the sides of the face, as they are intended merely to

steady the head in traveling. If there be any discharge of liquid from the eyes,

nose or mouth, which often occurs from the constant shaking of the cars, wipe

it off gently with a cotton cloth, slightly moistened with water. This body was

received by us for embalmment in pretty good condition, the tissues being

slightly discolored. The embalmment is consequently good. . . . The body will

keep well for any length of time. After removing the coffin lid, leave it off

for some time, and let the body have the air.”

Later, I couldn't help but read this passage aloud at several book events.

It seemed almost like poetry, its vivid phrases, simple words and quiet pace

instructing but also mesmerizing. Audiences listened in rapt silence. And the author of the note stuck the landing. After reading

that final phrase, “. . . and let the body have the air,” I had to take a

breath. The audience often murmured.

For all its practical advice, this little poem conveys the meaning of the

Civil War as well as any of the many gory accounts of death in battle I’ve

read. It connects the dead with those who mourn them – the “friends who open

this coffin.” Defying reason, it turns the mind to the notion that the corporeal state is eternal. “The body will keep for any length of

time.”

The letter that woke this memory was provided by my

friend David Morin. It was recently published with

substantial genealogical information on Cow Hampshire, a New Hampshire history

blog.

|

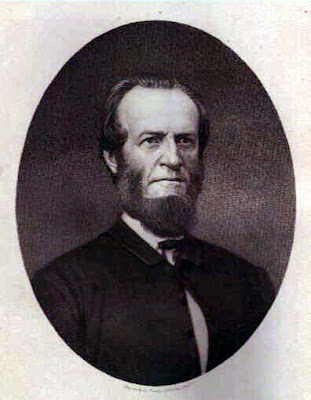

| Amos. S. Billingsley (1818-1892) |

Amos Stevens Billingsley, chaplain of the 101st Pennsylvania Volunteers, wrote the letter. Billingsley, a Presbyterian minister and missionary before the war, had

been captured and held at Libby Prison in Richmond in 1864. After his release he

was assigned to the Union military hospital at Fortress Monroe on the tip of

the Virginia peninsula.

The subject of Billingsley’s letter is Orvis Fisher, a 1st New

Hampshire Cavalry private who had a short yet fatal term of service. A father

of four from Fitzwilliam, N.H., he enlisted on March 22, 1865, and began to show

symptoms of meningitis three weeks later.

Here is Billingsley’s letter to Fisher’s wife, written on

April 20, as the Union army was ending the last hopes of the Confederacy. Billingsley seemed to be under

some regulatory obligation to withhold the date of Fisher's death from his wife, Sarah. It was April 18. Billingsley employs the standard biblical balm. but like the embalmers’ instructions to the friends and family of Miles

Peabody, his letter seeks to soothe with reassuring details about Fisher’s earthly remains.

U.S. General Hospital,

Fortress Monroe, Va.

April 20th, 1865

Mrs. O. Fisher

Bereaved Friend,

Man being born unto trouble this life is full of trials, yet

in all the Saviour says “Be of good cheer, let not your heart be troubled.”

Only trust in God and He will make all things, all these trials, afflictions

and loss work together for your good. Rom 8:28.

|

| Orvis Fisher |

These remains may be procured in the following manner. You

have only to leave an order with the nearest Express office whose Agent will

cause the body to be forwarded from here to any address you may furnish him.

The expense of this may be learned at the office as the Co. assumes the charge

of the entire business. The same person, who has the charge of the burials,

sees to the disinterment of bodies for transportation. By writing to Dr. E.

McClellan you may obtain receipts to sign and return, after which you will

receive the effects of deceased, if any there be.

The exact date of death we are not at liberty to give, but

it may be had by addressing the Adjt Genl at his office, Washington. A lock of

his hair was preserved which you will please find enclosed. I saw him often on

his death-bed, but he was unconscious, so much so that I could not get an

expression of his religious feelings.

He was so for a week ere he died, says the Ward Master who

wrote you several days since his death. . . . May God comfort you in this sad trial.

Your Sympathizing Friend,

Chap. A.S. Billingsley

*

Fisher’s body was later moved to Hampton National Cemetery

in Virginia. Sarah Fisher received a pension and a stipend for her two younger children.

.jpg)

.jpg)